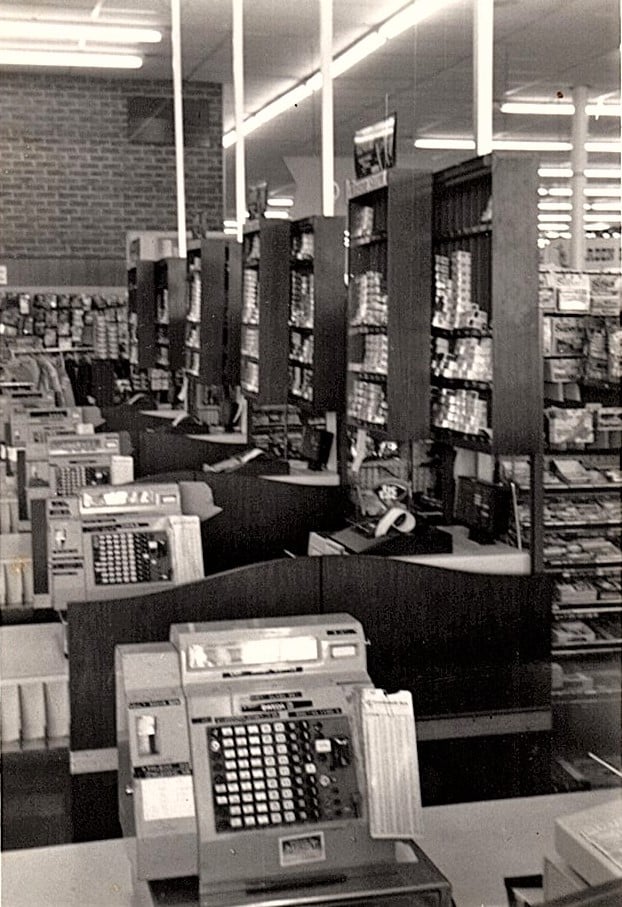

In the early 1980s (still researching the year), our local Ames was upgraded from mechanical Sweda cash registers to the IBM 3680 Programmable Store System. Our family was visiting this Ames on a roughly weekly basis. At the time layaway was handled up front at the Service Desk. The Service Desk normally had two Sweda Model 76 cash registers, one for refunds and one for layaways. Larger than the counterparts found at the regular checkouts, the Model 76 registers had more administrative buttons and printed receipts on double wide paper. The Model 76 registers could also print on forms, something the registers at the checkouts couldn’t do. Even though this Ames location had been open only a couple of years, the store had already outgrown the four checkout lanes and additional registers were on the end of the checkstands. During busy times the store would move two customers through one checkout lane at the time, one working at the normal register location, the other working on the end of the check stand.

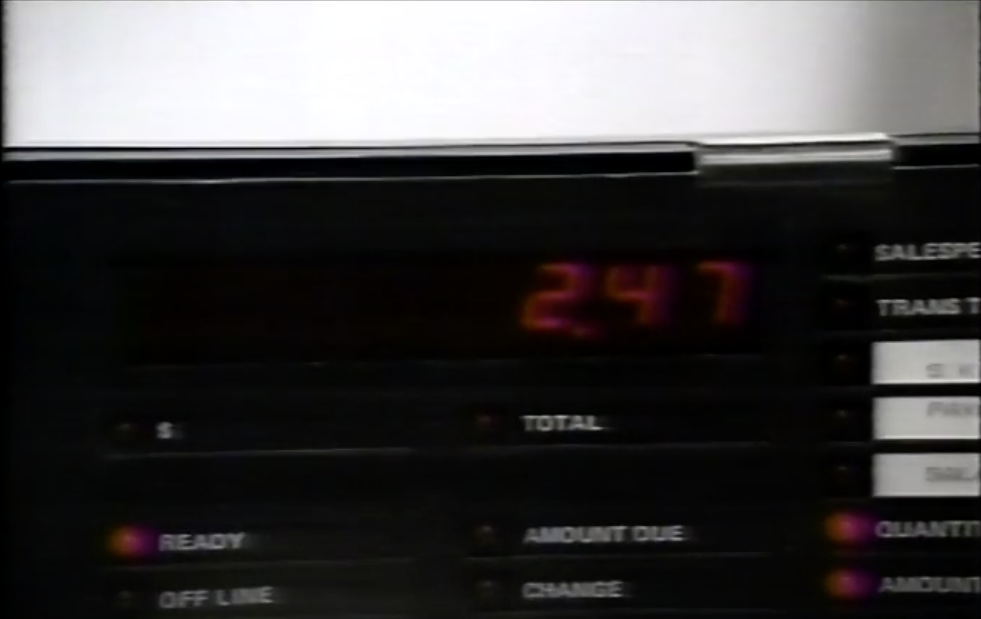

But back to the service desk. The geek in me immediately noticed a new IBM 3683 cash register installed between the two Sweda Model 76s. Powered up but with nothing on the customer facing display, this register wouldn’t be used for customers for a little while. Once in a while I’d see a person working on this new IBM register, but they didn’t seem to be assisting customers at the time, but rather just entering information from various paperwork.

I believe data entry was taking place in preparation for the impending conversion to electronic point of sale systems.

Our family was visiting towards the end of business hours on a Saturday when it was clear changes were taking place with the installation of new cash registers throughout the store. An IBM 3683 terminal was already sitting on the jewelry counter, the Sweda cash register was gone. There were boxes of equipment marked “IBM” below the checkouts. I recall overhearing a woman ask the manager of the store, “what are the registers on the end of the checkouts”? The manager replied, “I keep a couple extra around in case one of these registers break down.”

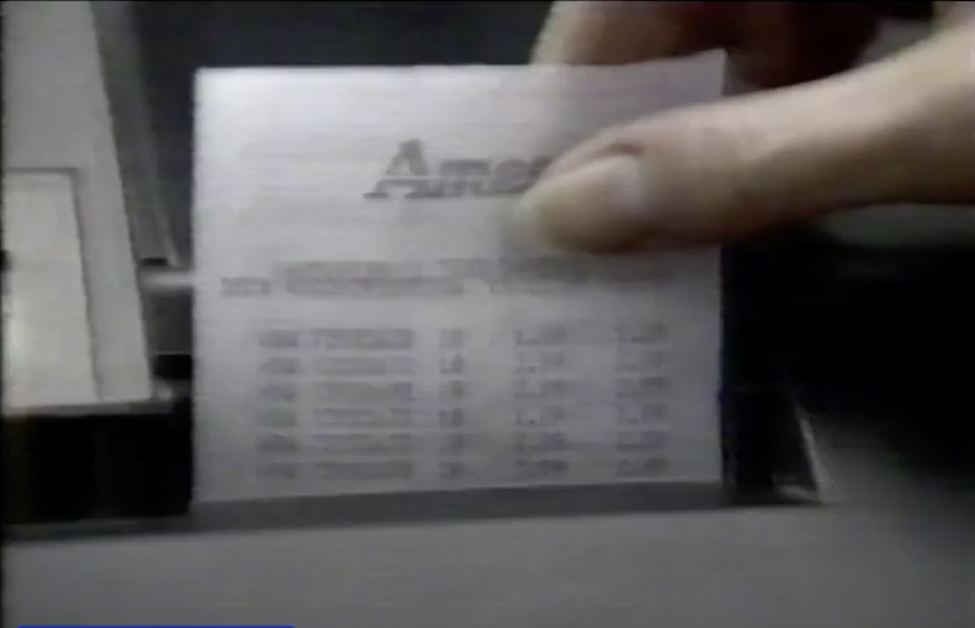

Curious about the IBM register sitting on the jewelry counter, I walked by slowly to take a look. There was receipt paper hanging out of the register; it looked like a tech was doing some testing. This was the first time I saw the Ames logo printed on a register receipt.

I was excited to know the next time we went to Ames they’d probably be using these new IBM machines that were being unboxed and installed.

It would take a few visits for me to get to know the functionality of these machines by sight and sound. I would take notes, look at receipts, and try to figure out what was going on. Scanning was still in its infancy and most relegated to supermarkets at the time. Ames went with an eight digit SKU (stock keeping unit) system, which was entered by hand, followed by the item amount.

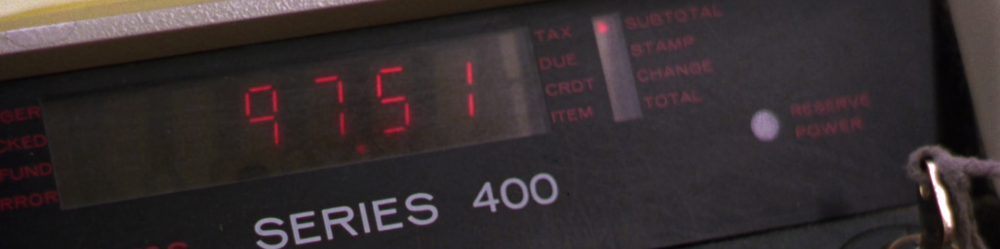

The keypad was calculator style, with 7-8-9 along the top. CLEAR was a double-height key on the first left-hand column of keys, in parallel with the zero and 1-2-3 rows. To the right of CLEAR was Modify Ticket. SKU was to the right of the number pad, parallel 7-8-9 and the function keys above the number pad, QTY below that, and ENTER / CASH to the right of 1-2-3 and the zero row. Tender keys were to the right of these keys, with SUBTOTAL and TOTAL all the way on the right in the lower two right hand positions of the keyboard.

Like some cashiers on the Sweda mechanical cash registers, some pressed SUBTOTAL then TOTAL, others just pressed TOTAL.

When the IBM 3680 system was first brought to Ames #80 the cash drawer wouldn’t pop open immediately after the cashier hit the type of tender key, a few lines of the receipt would print first, then the drawer popped open. This was changed within the first year of the system being adopted here, where the drawer opening was moved to be instantly after the CASH tendered key was pressed. This was the way it was when I worked at another Ames store in the late 1980s.

One function that seemed to trip up cashier quite a bit was having to select the type of transaction for every sale. Curiously, Ames cashiers had to press the MODIFY TICKET key to start a sale, when the TRANS TYPE light was illuminated on the display.

While I have yet to locate documentation for the IBM 3680 Programmable Store System, the early IBM 3650 Programmable Store System also had a Modify Ticket key, which was used by cashiers to indicate they wanted to change the price on a “wanded” item. Normally, when TRANS TYPE was illuminated, a cashier would have pressed “1” for CASH SALE, but for some reason Ames decided to use the Modify Ticket key for this.

It would be a few years before the registers would have the capability of knowing an item price by SKU. Originally the registers would know if an entered price was too low or too high for the entered SKU. This was based on the first three digits, which was the class number of the item.

Ames’ eight digit SKUs were all based on the original two-pass class/SKU entries on the older mechanical registers, and many items were marked with both during the transition to the IBM system. Whereas the punch tape version used a three digit SKU, four digit SKUs were introduced with the conversion; one can assume it was to accommodate chain growth. Hence, the SKUs introduced in the IBM conversion were actually the three digit class + a four digit SKU + one digit as the Modulus 10 checksum digit. For example, a price ticket would have a top line of 112 237, second line of 23701121, and then the price. On the Sweda register, pass one would be 112, pass two would be 237.

Entered SKUs had to pass the Modulus 10 check unless they were “generic” SKUs, which was the class number padded with zeroes. I believe the registers were not validating an entered SKU on the backend, rather, it was making sure it passed the modulus 10 checksum. At first it looked like cashiers had to “fill up the screen” with zeroes when entering generic SKUs. Before candy bars were 67235515, they were originally entered as 67200000. The LED display on the register held eight digits at a time; longer numbers (like credit card numbers) would simply scroll off the screen as they exceeded the width of the display. In later years, cashiers could pass a generic SKU with 7s instead of zeroes.

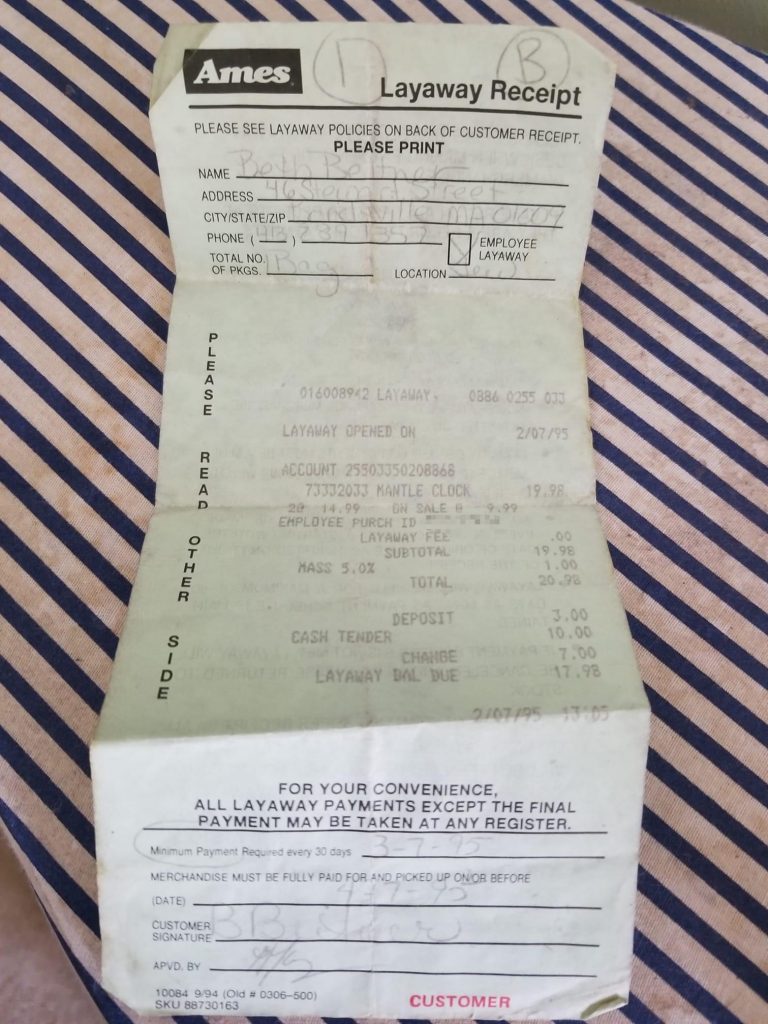

The one thing I could never reverse engineer from the receipts was all of the data included in the “DOC #” at the top of a receipt. Like other point of sale systems of the time, the receipt contained the store number, the transaction number (usually four digits), the cashier ID number, and the date and time. But Ames also printed a DOC #, which restated all this information, along with other information, in one long numeric string.

A typical DOC # would be something like 08000116512346, where:

- 080 is the store number

- 001 is the register number

- 1 is the transaction type (here it’s cash sale, 5 would be layaway)

- 65 – never figured it out

- 1234 – transaction number

- 6 – Modulus 10 checksum digit

When Ames acquired Zayre in 1989 and began replacing their NCR 2552 registers with IBM 4680 General Sales Application, the receipts were much more like other stores using IBM 4680 at the time and they didn’t include the DOC # like the 3680 PSS registers did. However, a layaway transaction at a former Zayre location did use the same scheme for the Layaway Account Number.

It was Ames #80’s migration to the IBM 3680 Programmable Store System that kicked my interest in computers, point of sale systems, and software engineering into high gear. When I worked a few months around the holidays at another Ames store in 1989, Ames was pretty much still using the same software with a few upgrades here and there.

It would be a couple more years before Ames would add scanning to the 3680 Programmable Store System.